For years, Holocaust survivor Pinchus Gutter has told the tragic story of watching his parents and 10-year-old twin sister herded into a Nazi death camp's gas chambers so quickly that he had no time to even say goodbye.

He was left instead with an enduring image he has carried with him through 70 years: that of his sister vanishing into a sea of people doomed to die.

Only this time the elderly, balding man wasn't really there as he recounted the horror of the Holocaust to an audience gathered in an auditorium at the University of Southern California's School of Cinematic Arts.

It was the 80-year-old survivor's digital doppelganger, dressed in a white shirt, dark pants and matching vest, that was doing the talking as it gazed intently at its audience, sometimes tapping its feet as it paused to consider a question.

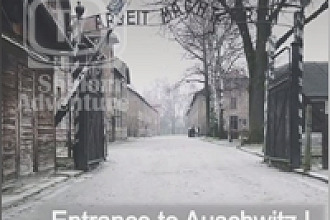

Over the years, elderly Holocaust survivors like Gutter have been leaving behind manuscripts and oral histories of their lives, fearful that once they are gone there will be no one to explain the horror they lived through or to challenge the accounts of Holocaust deniers like Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

For the past 18 months, a group led by USC's Shoah Foundation has been trying to change that by creating three-dimensional holograms of nearly a dozen people who survived Nazi Germany's systematic extermination of 6 million Jews during World War II.

Like the digital librarian portrayed by Orlando Jones in the 2002 movie "The Time Machine," the plan is for Gutter and the others to live on in perpetuity, telling generations not born yet the horror they witnessed and offering their thoughts on how to avoid having one of history's darkest moments repeated.

Although people at this week's event saw Gutter as only a two-dimensional figure, he has been painstakingly filmed for hours in 3-D and, perhaps as early as next year according to those involved in the project, his hologram could be talking face-to-face with visitors at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

Certainly it will be within five years, said Stephen Smith, the Shoah Foundation's executive director, and Paul Debevec, associate director of the university's Institute for Creative Technologies, which is creating the hologram project's infrastructure.

“Having actually put it together, it’s clear this will happen,” said Debevec, whose institute has partnered with Hollywood on such films as “Avatar” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” winning a special Academy Award for the latter.

Indeed, it already has almost happened.

More than 15 years after his death, rapper Tupac Shakur made a 3-D hologram-like appearance at last year’s Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, performing alongside a real Snoop Dogg. Technically, Shakur wasn’t a hologram, however, because his image was projected onto a thin screen that was all but invisible to the audience.

“This takes it one step further as far as you won’t be projecting onto a screen, you’ll be projecting into space,” Smith said of the project, called New Dimensions in Testimony.

It comes just in time, said Rabbi Marvin Hier, director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, which is dedicated to keeping alive the history of the Holocaust.

“This generation is coming to an end, unfortunately,” Hier said of Holocaust survivors, whose average age is estimated at 79. “Within the next decade or so there won’t be many survivors alive anywhere in the world.”

Given the prominence of Holocaust deniers like Iran’s Ahmadinejad, Hier said, it’s crucial to record survivors’ accounts in a way that future generations can easily access and relate to.

“The Holocaust is well documented, and we have confessions of the major war criminals,” he said. “But there’s nothing like the human witness who can look you in the eye and say, ‘Look, this is what happened to my husband. This is what happened to my children. This is what happened to my grandparents.’”

Developing a technology capable of that has been painstakingly time consuming. But in the past two years, researchers say, it has come together faster than they once imagined.

To help in the effort, Gutter had to sit under an array of hot stage lights and in front of a green screen for hours at a time over the course of five days, answering some 500 questions about himself and his experiences.

Research scientists at USC are still editing them and working with voice-recognition software so that his hologram will not only be able to tell his story but recognize questions and answer them succinctly. Being able to do that often required asking as many as 50 follow-up questions to one of the original ones, Smith said.

While researchers have found there is generally a range of about 100 questions people ask survivors of the Holocaust, if someone in the future comes up with one Gutter’s hologram can’t answer, it will simply say so and refer them to someone who might know.

For the demonstration shown this week, he sat before seven cameras. For the final hologram, more than 20 will be placed at every angle possible, so he will appear to people standing or sitting anywhere in the audience just as he would if he was really there.

No pepper screen will be used to display his hologram, as was the case with Shakur. Instead, it will be broadcast into open space, allowing people to approach and interact with the hologram just as they would a real person.

Eventually, according to Debevec and other researchers, holograms could come to have numerous uses. Among them would be teaching classes, taking part in business conferences and providing expert opinion on subjects when real people can’t be there to do so. They could even be used as teaching tools for people studying to become therapists who aren’t quite ready to work with a real, emotionally troubled person.

For now, however, researchers are working strictly with Holocaust survivors, creating a list of nine other people with the help of the private group Conscience Display, which records survivors’ stories and suggested the project.

Given that every person interviewed has been 80 or older, Smith said, it may prove difficult to find subjects with the stamina to participate. Still, no one approached so far has said no to the idea.

Perhaps Gutter’s digital presence summed up the reason for that best when it was asked the other day why he chose to take part.

It replied: “I tell my story for the purpose of improving humanity.”…

Originally found here