Many factors made Jewish resistance to the Nazis during the Holocaust both difficult and dangerous.

At first, most Jews believed they would be re-settled to a productive life. Many Jewish leaders believed that by working for the Germans they could survive and limit the suffering of other Jews. As fear and terror became everyday truths for most Jews during the Holocaust, standards of daily reality shifted dramatically. One reality that could not be overlooked was the power of the German army.

The superior, armed power of the Nazi regime posed a major obstacle to the resistance of mostly unarmed civilians from the very beginning of the Nazi takeover of Germany. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, Poland was overrun in a few weeks. France, attacked on May 10, 1940, fell only six weeks later. Clearly, if two powerful nations with standing armies could not resist the onslaught of the Germans, the possibilities of success were narrow for mostly unarmed civilians who had limited access to weapons. The Nazis also created and used the idea of "collective responsibility" to thwart resistance.

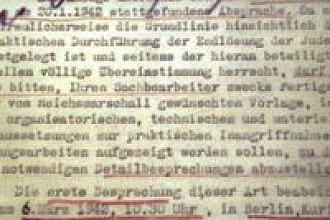

The pamphlet produced by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Miles Lerman Center for the Study of Jewish Resistance entitled Resistance During the Holocaust describes the German tactic of "collective responsibility." This tactic held entire families and communities responsible for individual acts of armed and unarmed resistance. In Dolhyhnov, near the old Lithuanian capital of Vilna, the entire ghetto population was killed after two young boys escaped and refused to return. In the ghetto of Bialystok, Poland, the Germans shot 120 Jews on the street after Abraham Melamed shot a German policeman. The Germans then threatened to destroy the whole ghetto if Melamed did not surrender. Three days later, he turned himself in to avoid retaliation in the ghetto. One of the most notorious single examples of German retaliation as punishment for resistance involved the Bohemian mining village of Lidice and its 700 residents. After Czech resistance fighters assassinated Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, the Nazis retaliated by "liquidating" nearby Lidice, whose citizens were not involved in the assassination. The Germans shot all men and older boys, deported women and children to concentration camps, razed the village to the ground, and struck its name from the map.

The speed, secrecy, and deception that the Germans and their collaborators used to carry out deportations and killings were intended to impede resistance. Millions of victims, rounded up either prior to mass shootings in occupied Soviet territory or for deportation to Nazi killing centers where they were gassed, often did not know where they were being sent. Rumors of death camps were widespread, but Nazi deception and the human tendency to deny bad news in the face of possible harm or death took over, as most Jews could not believe the stories. The German or collaborating police forces generally ordered their victims to pack some of their belongings, thus reinforcing the belief among victims that they were being "resettled" in labor camps. As the sense of death's inevitability became abundantly clear, the youth of the Jewish political movements began to organize armed resistance against the Germans. This is evident in the Sobibor Concentration Camp and the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Such resistance was as much an act of desperation and an open expression of defiance as it was an act of real self-defense. The overwhelming power of the German regime coupled with collective punishment and the thorough means of deception played on the Jews all contributed to the reason so few Jews fought back and why there were few organized resistance groups.

Posted on Shalom Adventure by: Brenda Miller

Originally found here

Picture originally found here